The mass-demass cycle is as follows: technology or media is created by a group of pioneers who collaborate in order to use and popularize the new technology or media, the technology or media is then taken over by a small number of powerful people (i.e. corporations), who in turn, present it to an audience, which then reclaims the media or technology as their own and begins to create with it. This is significant in terms of participatory culture because it explains the methods through which technologies and media are obtained. Blogging is different from this mass-demass cycle because it began in the hands of the people and continues to be an accessible technology for the people, as most blogging can be done for free (though there are corporations that are involved). Halavais describes blogging as a "free frame of reference" because it is a simple act that helps the user to reframe their way of thinking about the world. Blogging is an accessible format for discourse that almost anyone can use. When there is a free, accessible discourse format, the opportunity for radical sociopolitical change presents itself.

"Free frame of reference" originated in the late 1960s as a store where all of the items were free. The store had essentials such as food and clothing, and the "frame" was in reference to "a large yellow picture frame" by the entrance (Halavais, 114). The store revolutionized the way that its "customers" thought about consumption and the value of items in our society.

I can not say that I agree entirely with Halavais in terms of the perspective demanded by blogging. Self-expression has always been accessible in one public format or another, blogging just magnified the scale and audience. I believe that, with the diversification of blogging, it has still maintained its spirit as a free frame of reference. Very few people are willing to pay actual money to blog, whereas as few years ago, people would pay quite a bit of money in order to keep and maintain a professional blog. Now, there are more ways than ever to express oneself freely through the Internet.

The ideal is tarnished, though, through the commodification of blogging. In order to be a true "free frame of reference" profit would not be an issue. Now blogging sites are able to make money off of their users through the use of advertising. Yes, the users may not have to pay directly, but they are still being used for monetary gain.

Equality within the attention economy is a difficult idea to navigate. Perhaps equality within the attention economy would be an egalitarian format in which each person gets their say for the same amount of time among the same number of people.

Social media as gemeinschaft would be the use of free blogging among a group of people to organize a social protest. Social media as gesellschaft would be the requirement of monthly subscription fees for a website in order for the few people in charge to make a profit off of it.

Thursday, April 30, 2015

Tuesday, April 28, 2015

Monday, April 27, 2015

Fuchs Ch 8

In Chapter 4 of Social Media: A Critical Introduction, Christian Fuchs explores the connections between Twitter and political participation. While reading, I started to think about the potential of repurposing aspects of Twitter to be geared more toward political activism and change. Fuchs states that, on Twitter, the topics that attain the highest visibility (as demonstrated by the Trending Box on the left-hand side of Twitter) are those that pertain to entertainment-related topics. However, I started to explore the idea of tailoring Twitter to be used as a political tool. For example, the Trending Box could be separated into subcategories, including Entertainment and Politics. This would allow for higher visibility within each category, therefore preventing the domination of visibility of one category over another, therefore facilitating political visibility within the interface of Twitter itself.

Later, Shirky states that “with the arrival of globally accessible publishing, freedom of speech is now freedom of the press, and freedom of the press is freedom of assembly (Shirky 2008, 172). This statement resonated with me because I began to think about both the benefits and downsides of online political culture. I see the value of social media in politics the same way as Papacharissi interprets it - the idea that social media eradicates the line between the political and public spheres. I think that a greater visibility from a grassroots level is key to political change. I also think that, at times, the anonymity offered by the internet is beneficial in terms of political participation. It allows one’s voice to be heard, without suffering social repercussions from their peers or even an oppressive government. However, one downside to online political participation is that in person, physical spaces allow for an agglomeration of individuals that “provide opportunities for building and maintaining interpersonal relations that involve eye contact, communication of an emotional aura, and bonding activities that are important for the cohesion of a political movement and can hardly be connunicated over the internet” (186). So, at the end of the day, there are certain shortcomings of online participation that simply cannot be overcome or overshadowed by in-person, face-to-face, political movements.

PCH Chapter 28

Chapter 28 of The Participatory Cultures Handbook, edited by Aaron Delwiche and Jennifer Jacobs Henderson, explores the ethics of participatory culture. In her essay entitled “Toward an Ethical Framework for Online Participatory Cultures,” Jennifer Jacobs Henderson first defines participatory cultures as “spaces where thoughtful, engaged world citizens tackle complex problems, build creative networks, and contribute to political decision making” (272). Henderson then goes on to describe the potential that these spaces can achieve, such as advancing scientific discovery, empowering those who have little voice, and the elimination of geopolitical boundaries (272). However, in order for those potentialities to occur, ethical structure must first be assigned to participatory culture. To do so, Henderson establishes five fundamental aspects that must be assigned - access, rule making, connectedness, contribution, and freedom.

According to Henderson, two barriers to active participation have existed for many years - income, and geography. However, the recent development of new technology hasn’t remedied these two barriers. It has simply perpetuated their existences, but in a new way. For example, wealthier countries have more widespread internet access compared to less wealthy countries, which does nothing but perpetuate the “digital divide” (273). In my opinion, however, barriers extend beyond income and geography. Another barrier that exists is technological literacy, or the lack thereof. Technological illiteracy prevents members from taking advantage of the participatory technology, so that even if they have the physical access to it, they are unable to use it in a meaningful way.

Henderson then asserts that another structure that must be enacted is rule making. She acknowledges that these rules may differ based on the medium at stake - the rules governing original uploads may differ from the rules governing comments. However, regardless of the specific rules being applied, she argues that these rules must be enforced if participatory culture has any chance to thrive.

Henderson continues with her structural establishment, emphasizing the importance of both connectedness and contribution. In my opinion, participatory culture inherently involves a sense of commonality and connectedness. Henderson advocates for these aspects of participatory culture to be even more developed and encouraged within the community in order to facilitate the survival of the culture. She also values the aspect of contribution, stating that “respect must be at the core of valued participation” and that this respect is “often attained through recognition by others” (277).

Finally, Henderson develops the idea of freedom in participatory cultures, and asserts that a wide range of voices and opinions must exist in order for the full potential of participatory culture to be reached. Wark Review

In his newest book, The Spectacle of Disintegration, McKenzie Wark continues the situationist-centered dialogue he established in his preceding book, The Beach Beneath the Street. Both books serve as analyses of the Situationist International, delving into their history, beliefs, and practices. Founded in 1957, the Situationist International (SI) was an international organization composed of social revolutionaries. Membership was extremely exclusive. The demographics of the members themselves varied - the organization was composed of artists, political theorists, intellectuals, and more. However, the one thing that united the members of the Situationist International was their shared social ideology.

In The Beach Beneath the Street, Wark recounts the first two aspects or phases of the Situationist International - the artistic phase during the 1950s, and the political action phase in the 1960s. He also elaborated on the first two facets of the spectacle. The first facet was concentrated spectacle. This was the period when society, and power by extension, was organized around a central personality. Later, the diffuse spectacle emerged. This type of spectacle influenced society by the use of icons and advertising in order to sell commodity. Additionally, the idea that the meaning of life could be achieved via consumption was emphasized and built upon.

In The Spectacle of Disintegration, he goes on to elaborate on the third and most current phase of the organization - the phase of the spectacle known as the integrated spectacle. Although misconceived as the end of the SI movement, Wark argues that it is simply a re-manifestation of the core ideals, adapted to today’s society. In other words, Wark connects the past decades’ situationist theory and practice to today’s ideals. To do so, he focuses on situationists and their work. For instance, he analyzes the painter T.J. Clark, commending him for “restoring to view the life of the image and an anarchist vision” (48). Wark then goes on to the figure of Raoul Vaneigem, a Belgian member of the Situationist International from 1961 to 1970 whose main concern was the concept of utopia as well as dystopia.

Wark continues in chapter 9, exploring the society of the spectacle in the context of artistic pieces, namely the obscure Viénet film, Can Dialectics Break Bricks. It is here that Wark makes an argument that films such as these are simply remixes of films that had already existed. From this, Wark goes on to refer the audience to other Situationist pieces that stemmed from other existing artistic forms, thereby undermining their originality. He emphasizes the re-working and remanifestation of artistic elements into new constructions, yet simultaneously and confusingly asserts that nothing is innovative.

Finally, Wark explores Guy Debord, who was a French Marxist theorist and a founding member of the Situationist International. For some reason, the aspect of Debord’s life that Wark chooses to expand on is the development of the board game, Game of War, developed by Debord and his wife, Alice Becker-Ho. The connection between Wark’s extensive development of the board game and the Situationist International is unclear and extremely vague, making it difficult to understand.

Overall, I would not recommend this text as a source for teaching participatory culture. The writing itself is very cryptic and dense, making it fairly inaccessible to a general audience, even more so to those who are not well-versed in the realm of situationist theory. In addition to the difficulty of reading the text, Wark’s main tool in his writing is the use of endless quotes. While reading, it felt like I was simply reading the work of the people Wark described in his book, simply stitched together. By doing so, Wark failed to contribute any original information or insight into the Situationist theory community, and merely summarized and repeated the thoughts of situationists who had already expressed their views. Even if Wark did contribute original insight, it would have been lost in the sea of quotes by other figures who actually did, thereby undermining Wark’s nonexistent arguments. Thus, although Wark is skilled in synthesizing information about the SI, I would not recommend this text if you are looking for new, original, and revolutionary information and insight into the Situationist International.

Wednesday, April 22, 2015

Tuesday, April 21, 2015

Wark Review

The Spectacle of Disintegration

by McKenzie Wark is based on the premise that the Situationist Movement did not

end when the Situationist International disbanded in 1972 and that it is still

alive and well in the modern world. To do this, Wark chronicles the history of

Situationism from 1968 on. Wark had already written The Beach Beneath the Street,

which discussed Situationism up to this point, which raises one of the main

problems with the book. Wark immediately dives into Situationism, assuming that

either we have read The Beach Beneath the Street or have extensive

knowledge of the Situationist Movement before reading this book. This is not a

stand-alone book by any means, but does not advertise that a reader will have

difficulty if they have no background on the subject. In order to get the most

out of this book, the reader needs to have a background in Situationism and 19th

Century French Are, both of which are specific and not particularly overlapping

areas.

The

structure of the book added to its inaccessibility. Each chapter was a separate

anecdote, and while some of these were quite entertaining, they did not clearly

connect into an overarching narrative. I understand that Wark purposefully

removed these anecdotes in order to make a theoretical agenda for Situationism

in everyday modern life in order to prove that it still is applicable today,

but this has the consequence of forcing the reader to pick up context along the

way. The anecdotes are so short that you can read a majority of one before you

know what is going on, then you have to reread it now that you have context to

fully understand what is being said.

All of these

anecdotes acted as metaphors for what Wark was attempting to explain, but

again, they required expert knowledge to comprehend. I had none of this

knowledge so I read and knew the meanings of the majority of the words I was

reading, but never understood what was going on. This was not for lack of

trying on my part, I did research on the Situationist International, but was

still rather mystified by what the spectacle, the central idea of the entire

book, truly was. Wark would have been well served by including an introductory

chapter that clearly elucidated the central tenets of Situationism at the very

least.

Eventually,

I began to understand the spectacle, the society that surrounds it, and what it

has become a little more. Initially, the concept of the spectacle was

centralized. Governments used media and images to control their population.

These governments more or less had a monopoly on the spectacle, but the rise of

Mass Media has decentralized the spectacle. Now, we are bombarded by images

from governments and corporations through a variety of media. The rise of the

Internet also gave more of a voice to individuals as well. All of this combines

to shape and control what we see as the norm. Even if we are not aware of it,

the spectacle shapes us and our perception of the world we live in. To

exemplify that the spectacle exists, Wark discussed two revolutions, one in France

in 1848 and the other in Thailand in 2010. The latter provides an example of

the spectacle in modern times. Radio broadcasts were used to incite the

revolution and bring about a change in the power structure.

While

I did struggle with this reading, I can see how it applies to the class. Wark

provides examples of people who are aware of the spectacle and use this

awareness to bring about change. These individuals participate in enacting real

change not only by calling for change, but also by changing how they live their

lives once they realize the spectacle and what those creating it want us to

think and believe. While it is one thing to be aware of the spectacle, it is

another to be able to break free from its control. I wonder if anyone truly can

be free of the spectacle. We are indoctrinated at such a young age and it is so

pervasive in our lives that I doubt that anyone can truly break completely free

from the control of the spectacle.

Monday, April 20, 2015

Wark Review

Krysana

Maragh

In what ways

was the Wark book, The Spectacle of

Disintegration, useful in understanding participatory culture in present

time?

This book

offers terrific insight about the key issues of modern society. People in

modern society have a tendency to believe that everything they see in the media

is good. The spectacle is the image that mediates relations between people. Wark

maps the historical stages of the spectacle from the concentrated, to the

diffuse, to the integrated, to the disintegrated. He argues that the media is

responsible for the misconception of the relationship between desires and

needs. As it relates to participatory culture as a whole, The Spectacle of Disintegration highlights a particular concept

that I find key to the understanding of the relationship between the two, “No

matter what happens her next day or next week, I just want to record the fact

that this actually happened.” (Wark, 204). This is modern day social media: a

constant updating of what is happening regardless of the level of impact it may

have. It happened, it is posted, and it is recorded forever.

In analysis

of the “spectacle”, Wark offers four categories total: the concentrated,

diffused, integrated, and disintegrated. The concentrated is to be understood as

the focusing of efforts to raise the status of one, equivalent to what we

understand to be a “media-whore”; the Kim Kardashians of the world. The

diffused is understood to be the converse of the concentrated where advertising

allows for public focus to be separated; the meaning of life is found

everywhere. The integrated spectacle is understood as the combination of church

and state meaning what we believe to be good mixes with what we are told is

good. The spectacle of disintegration is the attempt to separate these two.

Wark focuses

heavily on the Situationalist movement of the 1960s. The Situationalist

International movement led by Guy Debord was made up of avant-garde artists,

intellectuals, and political theorist. They examined Marxist theory and

capitalism with the understanding that shifts from individual expression through

first-hand experiences and fulfillment of desires to individual expression by

proxy inflicted significant damage to the quality of human life for both

individuals and society. Consumers are passive subjects ruled by their

commodities in the spectacle that is mass media. Wark also narrows in on the

role of the middle class. He centers on the ambiguity of the “new” and its

attraction for the avant-garde artists. There was a strong draw to this group

because an overarching image that depicted the masses had yet to be

established. Even the situationists had motive to represent this public’s

desires, frustrations, and boredoms and claimed these feats as a new frontier.

The power of the middle class was its ability to both command popular space and

consume it. This was the beginning of a new market of people and speaks

directly to idea of participatory culture.

Participatory

Culture is one in which the prosumer was birthed. The consumer is also the

producer. Thanks to modern advancements in technology, the ability to

contribute is shared by all whom have access and knowledge of social media. This

is considered a relatively low barrier for entry because of the wide-spread use

of platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. These also prove to be an integral

component to the notion of participatory culture as it encourages collaboration

and thus a connecting of people.

The role of

media today is overwhelming. Wark argues that the main problem of modern

society is that people often don’t understand the differences between desires

and needs because we often led to believe we need the items we see, i.e. the

biggest houses, the fastest cars. But we could and should do without as most

people do not possess the purchasing power to obtain these items. Wark’s

insight on the Situationalist movement provides the precursor to this problem

we are facing today. Our quality of life is defined by our fulfillment of

desires when in truth it should be defined by the fulfillment of need. But the

two are often confused. Wark offers an analysis of power but it is now in our

hands as prosumers in a participatory culture to set the new standard, one

where the things we record are regarded as art that reflects our times, much

like that of the Situationalists.

Wark,

McKenzie. The Spectacle of Disintegration. London: Verso, 2013. Print.

PCH chapter 23

PCH chapter

23

There has been a lot of debate about the uCreate initiative

from the Edge Project as discussed in chapter 23 of the Participatory Cultures

Handbook; one of the main issues of this project being anonymity and privacy. It

was concluded that pseudo-anonymity was the most beneficial for participants in

this setting because it allowed youth to be identified and take pride in their

work yet allowed distance from published material should it prove to be

damaging at a later date. Hiro posted the question: What is being done to

educate the younger members of society – minors who have never known a world

without Facebook, Twitter, and the like about the consequences of misbehavior

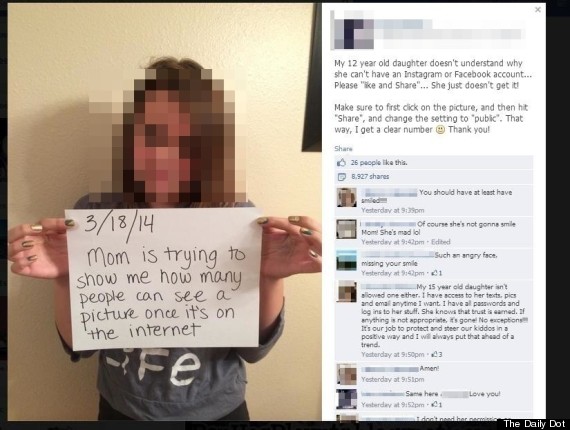

in the digital age? This question brought to mind this famous Facebook post:

Supposedly, in an attempt to educate her daughter about the

dangers of internet exposure a mother posted this picture to show just how many

people have access to anything posted online. I agree that the youth of today

are faced with a problem that previous generations have never dealt with,

establishing an online presence without tarnishing their identity. I think

awareness is the key to solving this issue. Acts such as the above picture that

physically show the theorized consequences are the best way to educate the

youth about their actions. Maybe it will prompt them to think twice before

posting content that would later prove to be incriminating.

PCH 28

In

this chapter, the claim is made that “the paired concepts of the ‘known’ and

respect relate directly to the concepts of the anonymous and untrustworthy in

online participatory cultures,” (277). We touch on the fact that there exists

valid ethical concerns regarding responsibility for words and actions and that anonymity

avoids these constraints but conclude that the contributions to the

participatory culture are significant but the identity is not. Ocean raised

this question on March 17, 2015: Can the real world knowability of a person

affect their respect within online participatory cultures? Nikki says yes so

long as those in the online realm know the real world identity of the

participant. I agree that knowing a person’s real world identity alters the

kind of content he or she feels comfortable posting. As previously stated, anonymity

provides escape from accountability. But I also agree that that the problem of

anonymity is the question of validity. It’s hard to trust the content provided

from an unknown source because we also don’t know that person’s motives in

providing accurate information. So to Ocean’s question about the relationship

between knowability and respect, I’d say the two a closely linked. An online

participatory culture could be led to believe they are following the thoughts

of distinguished philosopher about modern entertainment figures later to find

out the contributor is a Gossip Columnist who’s paid by the word. This person

would have motive to provide pages and pages of lies that stem from a single

sentence of truth, if any truths are to be found at all. By disguising his or

her identity and effectively removing the knowability component,

readers/participators are left with only the content to value.

Fuchs chp 4 and 8

Fuchs 4 and

8:

Fuch’s chapter 8 deals with the role of social media,

specifically Twitter and Facebook, in aiding with slacktivism. Slacktivism is

defined here as the kind of activism associated with social media that doesn’t require

people to make a “real” sacrifice or invest “real” effort in the promotion of a

cause. It’s remarked by Evgeny Morozo on page 188 as feel-good online activism

that has zero political or social impact and gives those who participate an

illusion of having a meaningful impact on the world without demanding anything

past joining a Facebook group. Josh Moran posed this question on March 17,

2015: is Fuch’s underestimating the power of these social media platforms?

I believe he is underestimating these social media platforms.

He makes the claim the Facebook and Twitter activism would only succeed in

situations that do not require people to make real sacrifice. Fuch’s mentions

in Chapter 4 that face-to-face communication and Facebook were activists most

important means of obtaining information about the Occupy Wall Street movement.

But he later goes on to dismiss this component as insufficient. I disagree with

this comment. I keep bringing to mind the KONY 2012 video that brought national

attention to the Invisible Children movement. In the course of a few days,

thanks to social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube, there

was such intense exposure of the video that the KONY website crashed. It was

later included among the top international events of 2012 by PBS and called the

most viral video of all time by Time Magazine. The purpose of the video was to

draw international attention to Joseph Kony, leader of an African Militia

serviced by refugee children and to have him arrested by the end of 2012. The

campaign resulted in a resolution by the United States Senate and contributed

to the decision to send troops by the African Union. I believe this stands as a

testament of the sheer power social media platforms truly possess. What some

believe to be mere slacktivism or clicktivism still aids in the cause.

Kelley and Mickenburg Presentation

For anyone interested, I've posted my presentation to my coursework page.

Wednesday, April 15, 2015

Tuesday, April 7, 2015

PCH ch 23 discussion

The Participatory Cultures Handbook discusses a lot of ideas about what participatory culture is and ways people can be a part of it. The ideas shared in chapter 23 were particularly interesting to me because they were an example of using participatory culture to help everyone benefit--being a democratic tool and not leaving certain people out. Chapter 23 discusses programs constructed to benefit and educate incarcerated youth. This is important because it exposes ways in which education is not democratic in our society. Because free education is available, on the surface it seems that education is a system that is beneficial to everyone. But this idea does not critique the fact that not everyone is given equal educational opportunities, nor does is acknowledge that some people are left out of the equation in general. A huge part of this is lack of resources available to some people, which explains the digital divide. Incarcerated youth, and people in general, are commonly viewed as unworthy of the expected benefits and treatment of people in society, including opportunities for education and jobs/careers. But the project discussed in chapter 23 aims to fix this problem to an extent. By using digital media to provide an educational setting for incarcerated youth, participatory culture is being used to close the digital divide and the participation gap, as well as creating a democratic space within our education system. By becoming available to and benefiting those who had previously been excluded from participating, the digital media described in chapter 23 displays an example to true participatory culture.

Wark Review

The

Spectacle of Disintegration: Situationist Passages Out of the 20th

Century by McKenzie Wark discusses the history and present day narrative of

the Situationists and the Situationism movement. The Situationism movement took

place between the 1950s and 70s and was led by an organization called

Situationist International, which was comprised of a group of intellectuals,

artists, political theorist, and social revolutionaries that sought to

challenge and critique modern society and its perpetual use of capitalism. Wark

argues that although the movement officially ended in 1972, it isn’t really

over and Situationist ideology is still present today.

Wark is

critical of people in modern society not knowing the difference between what

one needs and what one desires. As a consequence of capitalism,

people have fallen into believing they need material items as opposed to just

wanting them. He also believes that almost everything has become a part of

consumerism—for instance, his mention of sex once being a private act but being

transformed into a public market for buyer consumption. Wark believes mass

media/the government, or the spectacle, is to blame for this. The idea of the

spectacle was the most interesting part of the book in my opinion. The

spectacle is the relationship between people and the images shown in the media.

These images include material items and luxuries as well as images of people

(celebrities). These images seem to have control over the average person

because consumerism has become so engrained in every day life of those in

modern society. The idea of the spectacle is very relevant to today. Images

shown in the mass media definitely have control over many people because they

shape many people’s ideas. The mass media teaches people how to classify and

view things—whether it is: who is or isn’t beautiful, what is acceptable as a

career/job, what kind of car one should drive, how one should dress, how one

should view certain groups of people, etc. Many of Wark’s ideas and the ideas

of the Situationist coincide with Marxist theories.

While I am

biased to some of the ideas expressed in the book because of my personal

opinions about capitalism and modern society, I still had many problems with

this book. First and foremost, the book was written with the assumption that

the reader had previous and vast knowledge of French art. The book brings up a

lot of works of art, especially paintings, and explains their connection to the

Situationism movement. As somebody who doesn’t know anything about French art, this

aspect made some parts of the book hard to fully understand. In addition to

this, Wark speaks of the life and work of many people that are also not

commonly known to people who do not already have background knowledge on the

given topic. Although this book is a sequel, it still seems that someone

educated in the things that I have been educated in lacks much of the knowledge

needed to really get into the book without asking an overload of questions.

Despite

this, there were things that I learned from the book. I feel that I gained more

understanding of participatory culture by learning about Situationists

International because their goal was to use participatory culture to create a

more democratic and participatory society. By banding together as a community

with a common goal, the Situationists used participatory culture. Each member

of Situationist International contributed whatever he or she could offer in

hopes of changing the world. Their coming together to participate in a common

thing is similar to people that come together on the Internet to participate in

common interests, such as our class blog. By working together with the goal of

changing the world for the better, Situationist International was using

participatory culture in a beneficial way, which I think participatory culture

is about. Participatory culture aims to include everybody—to be inherently

democratic—benefiting everybody and not just elite groups.

Monday, April 6, 2015

Kelley and Mickenberg Powerpoint

Please go to joshuambloom.weebly.com and go under "coursework" to view the document.

Saturday, April 4, 2015

Wark Book Review

‘The Spectacle of Disintegration,’

by McKenzie Wark discusses the history, both past and modern, of Situationists

and their cause and movement. Within this book, Wark focuses on the

Situationist movement post-Situationist era. The book starts by giving you a

history of the movement, and really details Situationism from 1968 and on.

Though this book was full of information, it was very specialized for people

with backgrounds and knowledge of French art and culture and it’s ties with

Situationism. Further more, this book was entirely made of up anecdotes, and

unless you knew a good amount of information about the Situationists and their

history, you would be lost in reading, which I was. This book would be a great

second or third book to read about the Situationist history and movement, but

not for your first encounter with the ideals and thoughts behind the

Situationist movement.

My problem with this book was the

fact that it was so entirely based on un-explained notions, making it

inaccessible as it connected real life events and trends to specific knowledge.

The details within the book seemed to run together, as even after googling

information on Situationists; I could not comprehend their detailed yet

seemingly arbitrary stories connections to “situationists” ideas. This book

would be much easier to understand if the author gave some back story or

explanation of what exactly Situationists were and did, rather than just giving

example after example and making the reader sift for information.

Wark’s book

mapped the society of the spectacle, while tracing Situationist ideas and

occurrences and showing how they could still relate in our present day society.

The book starts off with an anecdote and then traces the history of

Situationism. In Chapter 2 of Wark’s book, he states that he has purposely put

anecdotes cut from their context to connect a theoretical itinerary to every

day life to prove that the Situationist theory is still applicable and alive

today. Wark points out in chapter one that today, our society relies on

consuming and buying, a much more consumer-based society comparatively to past

generations. Wark continues to state that this book is concerned with the

“third step” of taking three steps back to take one forward. This “third step”

is post May 68’ political defeat, and it works to continue to prove that the

Situationist movement is alive (Wark, 19-20).

The topic

of the Situationist idea of the spectacle was very interesting in Wark’s book.

The idea of the spectacle – government control through media and central

images, was shown through examples of daily life spectacles. Although it was

hard to decipher, the examples were very relevant. The spectacle is now quite

different from the original ideas of the term ‘spectacle.’ It is now much more

decentralized and in our every day lives via television commercials and shows,

advertisements on the Internet, magazines, social media, clothing, etc. And as

we absorb these images, ideals, and so called ‘norms,’ they become apart of our

lives and us. Wark shows how the spectacle has shifted and changed, but

continues to stay alive past the official “movement.” He also gave examples of the

revolution in 2010 in Thailand to show that there is still a more close to

original idea of the spectacle still in certain areas of the world (Wark, 27).

It

was interesting that Wark showed participatory culture through a history and

examples of a movement that wanted to change the ways of the world. It allowed

me to understand how beneficial participatory culture can be, but it also shows

that even though many participated through the decades, the Situationists did

not win and grand win, but rather were able to change their daily lives through

being aware of the spectacle, compared to people who allowed themselves to be

influenced and apart of the control of media, government, etc. The book also

pointed to things that could be fixed within society that would make the world

a better place – less corrupted. Although this book was not my first choice for

a read or textbook, it did allow for me to see specific participation in many

different cultures, as well as the idea of how participation can change.Thursday, April 2, 2015

Wark Review

The Spectacle of Disintegration by

McKenzie Wark seeks to explain the Situationist International (SI) movement

that occurred between 1957 and 1972. Although history states that the movement

is over, he argues that is it present in everyday modern life- people just do

not realize it. The situationists wanted to uncover the world for what it

really is, why it is so, what it should be, and how it should be changed. They

centered around this concept known as the spectacle, which can be described as

the mass media of images that surrounds the modern person as well as some of

his predecessors.

The

spectacle has changed over time, but overall, it has remained the same. The

concentrated spectacle was prominent toward the first half of the twentieth

century, and in some places, such as North Korea, it still exists today. It

focused around centralized states such as Germany and the Soviet Union during

these times, and how citizens were forced to obey what they were told. In this case,

the media were the communist leaders, and the people were forced to believe

that what they were told was true. Later, it became the diffuse spectacle-

rather than leaders telling the people what to do, the mass media produced a

set of prominent images that society convinced itself it needed to follow.

Needs became synonymous with desire, and the world became false- what the

people believed was necessary was only necessary because the spectacle told

them that it was. Today, the spectacle is disintegrated- not centralized, but

in our everyday lives. Advertisements, television shows, clothing- it is all

part of the spectacle. Once we see it, we absorb it into our lives.

Wark’s

purpose in writing this novel was to show how the spectacle persists even four decades after the movement “officially” ended. He uses revolutions in France

during the 19th century and in Thailand in 2010 as an example (Wark

27). In both cases, the peasantry staged a revolution against the leadership.

Mass media was used to spark these revolutions- in 1848 Paris, through artwork,

and in 2010 Bangkok, through radio stations.

This book

requires at least some knowledge of the SI movement before reading it. While

Wark explains the basics of it in the early chapters, it helped me to do some

research on the movement as well as the spectacle itself before moving further

into the book. If you understand the main concepts as you are reading it, you

are better able to connect his examples to the goals of the movement, which

explains why he uses the examples in the first place. However, if you were to

pick up the book with no prior knowledge of the movement (keep in mind, the

book is a sequel), it would be quite challenging to comprehend the material as

well as the overall point of the novel. The issue I have with his examples is

that he does not ease the reader into them- he throws a random situation at you

that seems completely random, but only after finishing the explanation of that

situation does he relate it to the SI movement and participatory culture.

Despite

some of the book’s odd examples, it allowed me to look at participatory culture

through a movement that aimed to change the world. This is related to our final

project in the sense that our goal in doing research and creating a website is

to spark a sense of alarm in the public sphere that there is a problem with the

world that needs to be fixed. After all, activism only follows exposure.

Perhaps the

most important thing I learned from reading this book was that I am

participating in participatory culture much more often than I thought- not

through Facebook, as Standage says, but through the spectacle. When society is

exposed to a new object, it is led to believe that the object is desirable, is

good, and is necessary. For example, every time I use or walk around with a

smartphone, I am conveying the message that smartphones are necessary for

survival. In previous times, as recent as ten years ago, people survived

without these devices. My ultimate question for Wark is: what would he like me

to do about this? Does he believe that if one person puts down their

smartphone, others will follow until the point where society reverts back to a

point where this technological need will not be necessary anymore? More

importantly, how would society be any better without this technology? Has

anything created by the spectacle been harmful to society?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)